Extreme weather events are becoming more prevalent. An intensified water cycle explains why.

Drought and deluge – they are two sides of the same weather coin.

A new report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) now links extreme weather events – which include both droughts and major floods – to increasing carbon emissions. The unwritten conclusion of the report? It’s all about the water. More heat in the atmosphere is pulling more moisture off the surface and wreaking havoc on the planet in different ways.

One of the report authors and research physical scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, Alex Ruane, explains it like this:

The water cycle is basically the way that we track moisture moving through the climate system. So it includes everything from the oceans to the atmosphere, the clouds, ice, rivers, lakes, the groundwater, and the way that those things move and transfer moisture and water from place to place.

So when we’re talking about the intensification of the water cycle, we’re basically saying things are moving faster. Air is pulling the moisture out of the oceans and out of the land faster. It’s moving more moisture from place to place on the planet. And when it rains, it can come down hard.

The fundamental difference is that there is more energy in the system. There’s more heat. And as the temperature goes up, there is an overall increase in the amount of moisture that the air is trying to hold. So that means when a storm happens, there’s more moisture in the air to tap into for a big, heavy downpour. It also means that when air moves over a region, it has the potential to suck more moisture out of the ground more rapidly. So the same phenomenon is leading both to more intensive rainfalls and floods and precipitation, and also to more stark drought conditions when they do occur.

Alex Ruane, research physical scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies

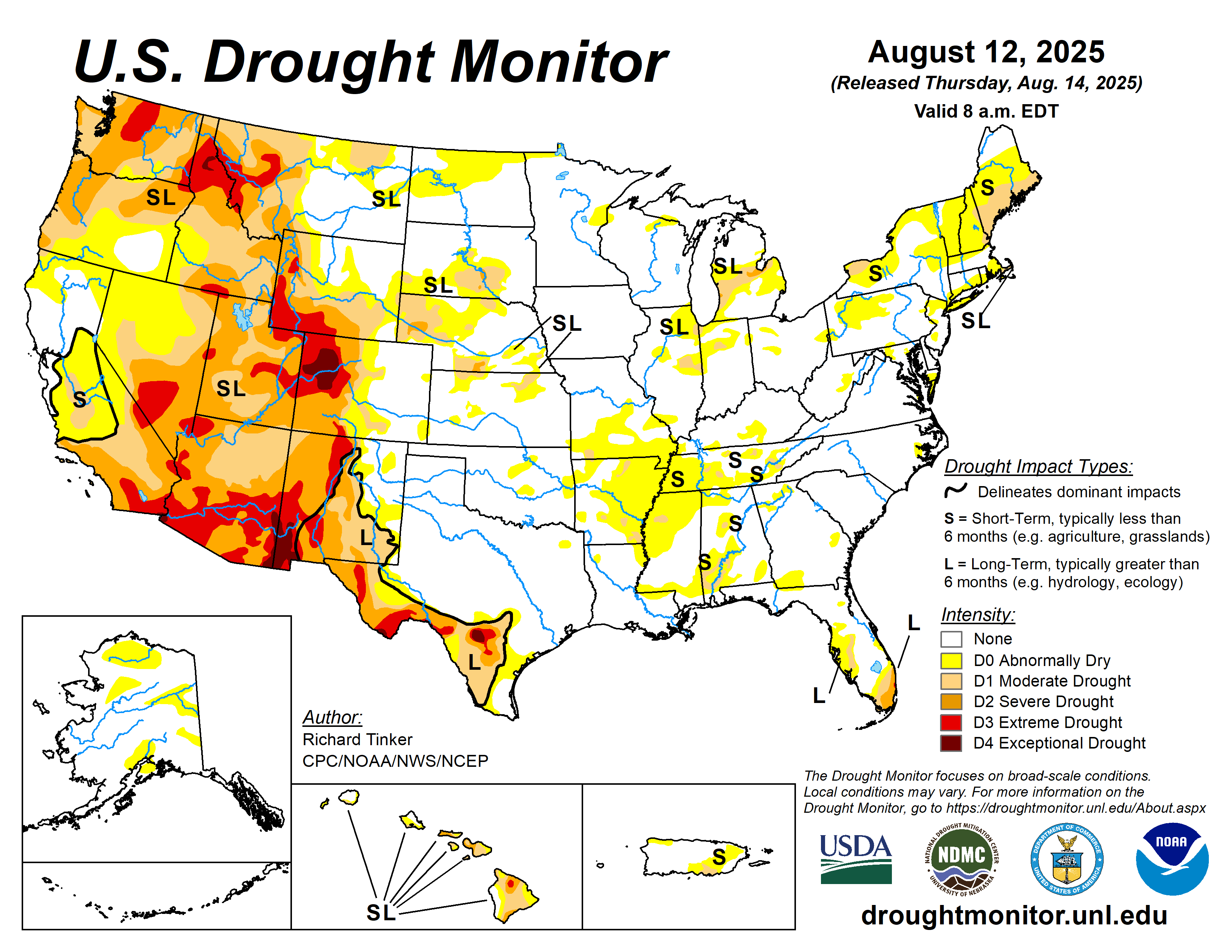

It would be irresponsible to say that some of the extremes the country has experienced lately – extreme cold in Texas, extreme heat in the Pacific Northwest, extreme drought currently impacting a large part of the country – are unique. Unfortunately, such events are becoming more commonplace. Storms, heat, floods and droughts are becoming more and more intense. The phrase “I’ve never seen it like this,” is uttered now more than ever before.

Research and modeling has gotten much better at linking extreme weather events to human activities.

Ruane explains that, “Methodological advances and several groups that have really taken this on as a major focus of their efforts have, in many ways, increased our ability and the speed at which we can make these types of connections.

“…Every year, the computational power is stronger in terms of what our models can do. We also use remote sensing to have a better set of observations in parts of the world where we don’t have weather stations. And we have models that are designed to integrate multiple types of observations into the same kind of physically coherent system, so that we can understand and fill in the gaps between those observations.

“…What the new report does is bring them all into one place and assesses them together, and draw out larger messages…And this is what the scientific community is showing us, that these things are part of a larger pattern of change that we have influenced.”

Droughts and floods (and other weather disasters) have always happened, but they are getting worse, and we are making them worse. While we can’t stop them, we can certainly stop the activities that are making them worse. Can we do that before the heat rises too far is the big question we must grapple with now.